Planning for Multilingual Learners in Math,

Part 1

by Vanessa Figueroa and Peter Tierney-Fife

As math teachers, when we are serving students from different countries—those whose parents studied outside of the U.S., or those for whom English is a second or additional language—we should take time to orient ourselves to their background knowledge and assets. It is through a growing understanding of who they are, and the resulting dialogue, that we can honor the “funds of knowledge” they and their families contribute to our educational system and to our math classrooms.

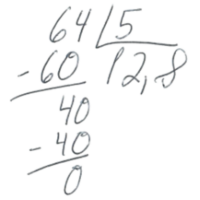

Vanessa remembers working on a division problem with two sixth-grade students who had recently arrived at her school from Venezuela and were both multilingual learners (MLs). She didn’t recognize their approach to long division. They wrote:

Their calculations were parallel to what she knew, but their notation seemed opposite. Instead of placing the divisor to the left of the dividend, as in 5⟌64, they wrote the divisor to the right of the dividend—and they wrote their quotient under the divisor rather than over the dividend. She then realized that “the standard algorithm” for long division is not so standard! This experience reinforced her awareness that the “U.S. way” is not the only way.

Discussing this notation difference with students emphasized the importance of language when communicating mathematical ideas and processes. It stretched Vanessa’s metacultural, metalinguistic, and metacognitive awareness. While this was a small moment, it motivated her to continue learning about and celebrating the diverse strengths and knowledge of her students.

This example, and the curiosity- and assets-based stance described, is an important foundation for planning math instruction that is supportive of students who are MLs. Although there is increasing understanding that mathematical sense-making and language competence develop simultaneously, and that supporting language development within math instruction is critical for MLs (and important for all students!), our educational system in the U.S. has positioned language and literacy mostly within the language arts domain.

The Problem with “Math is a Universal Language”

According to Gottlieb & Ernst-Slavit (2013), “Many educators consider mathematics a universal language partly because mathematics uses a set of symbols to express ideas using conventional English syntax” (p. 6). However, this assumption is not accurate.

Let’s take a look at the expression 3 (4 − x). A student might read it as “three times four minus x”. However, those words more accurately mean 3 × 4 − x, which is not an equivalent expression: the only value for x for which both expressions have the same value is x = 0.

To read, to understand, and to evaluate 3 (4 − x), one approaches it differently than when reading text in English from left to right. For any value for x, you can first subtract within the parentheses before multiplying by 3, or perhaps use the distributive property to multiply 3 × 4 and then subtract the product of 3 × x.

Reading the expression, listening to explanations about these concepts, thinking about the explanations, and explaining one’s thinking ALL depend on language that goes beyond numbers and symbols, and could include meanings that are not understood without explicit language instruction. For an example at a very basic level, if one were to describe an approach to solving the expression as “For any value for x, you can first subtract within the parentheses before multiplying by 3,” the number of words is seven times greater than the number of mathematical symbols and numbers (the variable x and the number 3).

Additionally, although the expression 3 (4 − x) may be written basically the same way by many people in the world, its usefulness in real life is greatly diminished without context or explanation, which likely includes language. How often do you, or adults you know, use JUST a math expression or an equation with no associated language, including your thoughts, at all? Thinking “math is a universal language” deters teachers from more proactively planning for the simultaneous development of math content and associated English language skills.

A related teacher mindset we’ve seen is the expectation that it’s the responsibility of the ESL/bilingual expert to support ML students with their language objectives in math classes—and that this support sometimes means translation only. Vanessa has spoken to many bilingual teachers who have stated that they were hired to translate content in classrooms when “pushing in,” or that translation is their “go-to strategy” all year. However, supporting students’ language development can and should be much more than translation and vocabulary support—and doing so is an important opportunity and responsibility for mathematics teachers also. In our experience, there has been a gap in professional learning for math teachers who serve MLs. Thankfully, there are an increasing number of resources available to help math teachers plan for the co-development of math and language.

Planning for Language Development During Math Lessons

There are two broad considerations when planning for English language development within mathematics lessons for your students who are MLs:

- Understand the mathematics language expectations for your MLs; articulating lesson-specific language objectives can be useful for planning.

- Adapt your lessons based on the mathematics language expectations, the lesson-specific language demands, and your students’ strengths and challenges.

Thinking through these elements as you plan will help you to choose adaptations that better support your MLs—and potentially all your students—in your math class. Ideally, planning for adaptations to support your MLs should occur collaboratively between ESL/bilingual teachers and mathematics teachers. Ongoing collaboration harnesses each others’ expertise and further builds knowledge and collective capacity. The Math for All lesson adaptation process is a perfect opportunity for this collaborative work.

Understand the Mathematics Language Expectations for MLs

The WIDA English Language Development (ELD) Standards Framework is a helpful resource for identifying and incorporating language development objectives for MLs. Most U.S. states have adopted the WIDA standards, and the framework provides explicit ways to connect language and math content by grade band, including language expectations and functions. For example, under English Language Development (ELD) Standard 3, Language for Mathematics, the framework specifies that students in Grades 4 and 5 should be working to construct mathematical explanations that incorporate describing their steps when solving a problem (WIDA ELD Framework, 2020, p. 118).

The language expectations are supported with additional information and actionable examples, such as students describing their steps using thinking verbs (e.g., remembered, figured out), using visuals to support their approach, and using connecting words (first, then, next) and relationship words (because, as a result) (WIDA ELD Framework, p. 119). The WIDA examples also sometimes include model sentences and sentence starters that can be used to support specific expectations.

In our experience, expectations for use of language in U.S. mathematics classes also derive from the mathematics register, which is the language and communication styles used by people who work in the field of mathematics. The mathematics register is complex, and it must be explicitly modeled and taught to students. The mathematics register has many components, including:

- Technical terms. New words (such as numerator) and new meanings for familiar words (such as table and yard);

- Syntax and organization. The structure of the language used to express mathematical ideas, such as the relationships between quantities (such as the same as), if-then statements, and ratio language;

- Oral and written instructions and explanations. How to approach problems and how to explain mathematical concepts;

- Extended discourse. The ability to argue and justify mathematical concepts using the language of mathematics.

The mathematics register is embedded in your curriculum materials, your mathematics standards, and your own background knowledge. When we think about how to support our students who are MLs (and all our students!) to sound more like mathematicians, we are essentially starting the process of reflecting on the language demands within a math unit, a lesson, and/or an assessment.

Lesson-Specific Language Objectives for Mathematical Language Development

When we better understand the high-level language expectations for our students in mathematics, we can more easily develop supports for lessons that go beyond translation and basic vocabulary instruction. Lesson-specific language objectives (Himmel, 2012) can be a helpful way to align and communicate the aspects of mathematical language that students will focus on. These specific language objectives may be included or implied in your curriculum materials, or you can derive them from considering lesson content along with the WIDA ELD standards, your knowledge of your students’ language strengths and challenges, and your students’ English Language Proficiency (ELP) level(s).

Asking yourself one or more of the questions below can help when writing lesson-specific language objectives.

- What are the relevant WIDA ELD standards, modes of communication, and key language uses for this lesson?

- What are the ELP levels of my MLs and what academic language support does this suggest is needed? Thinking proactively about their ELP levels can help you leverage your ML students’ strengths while also supporting their areas of growth.

- What language expectations do I have? What content-related language is important to learn?

- How can I ensure all my students think and sound like a mathematician during this lesson? For example, introduce an activity with a structured dialogue that includes academic sentence starters for students to apply in pairs.

When writing language objectives, make sure to consider expressive skills and oracy opportunities—ways to learn to talk and also to learn through talking. Oracy opportunities support development of both students’ interpretive (listening, reading, and viewing) and expressive (speaking, writing, and representing) skills. In general, we do our students a disservice if we focus exclusively on interpretive language objectives and strategies. However, at early stages of language development there is a focus on making “input” comprehensible and the development of students’ listening and reading comprehension (interpretive skills); this helps students at early stages to process both language and content successfully and simultaneously. As students progress through the continuum of language development, both in English and in their language other than English, the scaffolds should shift and/or be removed and a greater emphasis be placed on expressive language, including providing oracy opportunities.

Once you have named language objectives—ideally identified collaboratively, including between ESL/Bilingual teachers and mathematics teachers—you must adapt or select specific supports to use during that lesson to help students meet them. We will share specific strategies and related resources for this next phase of supporting MLs in your classroom in part 2 of this blog series.

References

Gottlieb, M. & Ernst-Slavit, G. (2013). Academic language in diverse classrooms: Mathematics, grades 3–5. Promoting content and language learning. Corwin

Himmel, J. (2012). Language objectives: The key to effective content area instruction for English learners. Colorín Colorado.

WIDA. (2020). WIDA English language development standards framework, 2020 edition: Kindergarten–grade 12. Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System.

The contents of this blog post were developed under a grant from the Department of Education. However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Math for All is a professional development program that brings general and special education teachers together to enhance their skills in

planning and adapting mathematics lessons to ensure that all students achieve high-quality learning outcomes in mathematics.