Math for All and Supporting Students’ Higher-Order Thinking

by Xue Han

Over the past few decades, researchers, educators, and policymakers have agreed upon the importance of fostering students’ higher-order thinking (HOT) in mathematics, which has led to reforming mathematics curriculum, instruction, assessments, and teacher training (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2000; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010). Developing higher-order thinking is essential for students’ success in learning mathematics.

Math For All employs a neurodevelopmental framework (NDF) to analyze the cognitive demands of mathematical tasks. This framework identifies eight key areas of cognition that can come into play when learning: language, sequential ordering, spatial ordering, motor functions, psychosocial functions, attention, memory, and higher-order thinking.

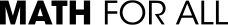

Components of Higher-Order Thinking

According to Barringer et al. (2010), higher-order thinking can be subdivided into five forms, each of which is highly related to mathematics learning and performance: thinking with concepts, problem solving, thinking critically, thinking with rules, and thinking creatively.

Thinking with concepts. Students are expected to understand, master, and apply mathematical ideas that build upon one another. A mathematical concept can be an abstract idea (e.g., regrouping) or concrete (e.g., polygons), verbal (e.g., vocabulary), or non-verbal (e.g., area model of multiplication). Thinking conceptually about an idea helps students remember facts and methods in mathematics, and students can easily reconstruct these facts and methods when they forget them. For example, you can’t add three quarters and two nickels without changing them to cents. Similarly, this same understanding is needed when combining fractions with different denominators; they have different units and must be converted to an equivalent representation with the same unit. This conceptual understanding prompts students to find a common denominator. Thinking with concepts also can help students generate new knowledge and skills for solving unfamiliar problems.

Problem solving. Problem solving is required when a solution to a task is not immediately apparent and requires strategizing and critical thinking. It also can require connecting multiple ideas or inventing a new approach to reach a solution. Once students identify and formulate the problem they have to solve, they must select strategies and tools. Problem solving is fundamental to mathematical proficiency and should be at the center of every mathematics lesson.

Critical thinking. Critical thinking is the idea that students don’t accept an idea or concept at face value. When presented with a mathematical idea, students analyze, evaluate, and reason about the information, and ask questions about the validity of the idea. Students may use critical thinking to justify their own ideas or disagree with others’ ideas, providing reasoning to support their arguments.

Rule-guided thinking. In mathematics, concepts get developed over time and through experience and can become rules that are accepted as truth. If you don’t understand the reasoning behind the rules, this can be an issue. However, using rules can be very helpful in solving math problems and can be an integral part of a process when used correctly. In a geometry context, for example, the rule is that if a shape is defined as a parallelogram, then you know that opposite sides are parallel and congruent, and that opposite angles are congruent. These facts can be helpful to show that the diagonals cut each other precisely in half.

Creative thinking. Many people regard mathematics as strictly rule-guided processes, but most of those rules have emerged from someone thinking creatively about a problem and asking, “What if?” This leads to exploration, often resulting in new ideas that are tested over time and either become established rules or are disproven. Students use innovative approaches through divergent thinking and risk-taking to solve problems and make sense of new ideas in mathematics.

Math for All supports teachers in understanding how students learn through the lens of higher-order thinking and enhances their ability to assess students’ strengths and challenges in this area. Teachers first engage in a math lesson hands-on, in the same way their students would. They then use the NDF to identify the HOT demands of the math task. Next, they observe students engaged in the same math task and analyze how they respond to the higher-order thinking demands, evaluating students’ strengths and challenges in the process. Based on the observations and analyses, teachers can plan and adapt future lessons to help students meet the higher-order thinking demands of future mathematical tasks and enhance their learning.

How Can Teachers Develop Students’ HOT in Mathematics?

To develop students’ higher-order thinking, teachers can consider the following strategies.

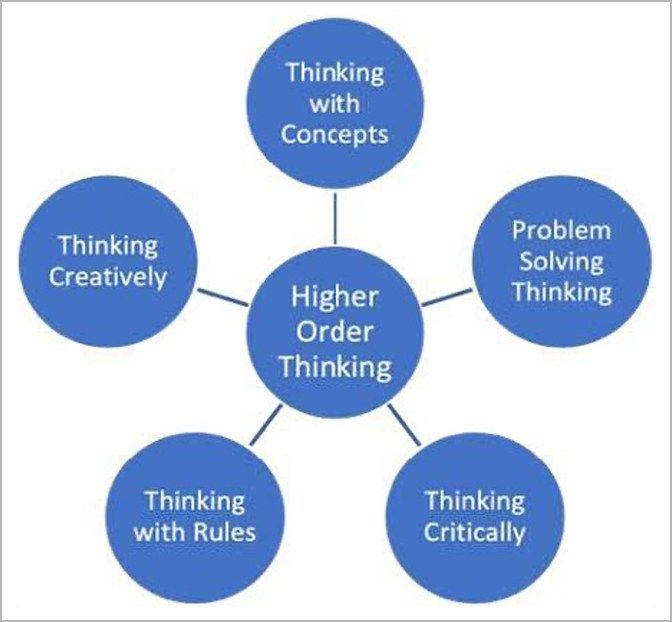

Select mathematical tasks that have higher-order thinking demands. Different mathematical tasks have various demands. For example, consider ½ + ¼ compared to asking students to identify a fraction pictured in the image to the right. The first task simply asks students to implement the standard algorithm after they have learned how to add fractions with unlike denominators. The second task places a higher cognitive demand on students because there are multiple pathways to arrive at an answer.

They have to draw on relevant prior knowledge and design a strategy. Mathematical tasks that require students to understand, analyze, and evaluate information, and then construct a solution method prioritize and develop students’ higher-order thinking skills. Lower cognitively demanding tasks require students only to memorize facts and follow established procedures to solve problems. Teachers can select mathematical problems with higher cognitive demands to engage students in higher-order thinking.

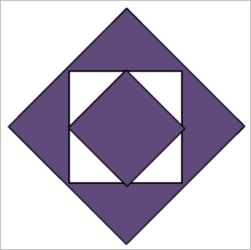

Use concept maps to show how concepts interrelate. A concept map is a diagram that illustrates the relationships among a set of related concepts centered on a central idea. Teachers can use this graphical tool to organize information and to represent structural relationships for students. Students can create their own concept maps that demonstrate their understanding of the relationships between critical mathematical concepts in a lesson or a unit. Through each student’s map, teachers can understand their mathematical thinking and identify and address any misconceptions they may have.

Encourage students to explore different mathematical representations. Concrete manipulatives, pictures, symbols, written and oral language, tables and graphs, technology (e.g., virtual manipulatives), and real-world situations all can be used to explain mathematical concepts and solve mathematical problems. Mathematical representations can help students visualize abstract mathematical concepts and ideas, enabling them to understand the relationships among concepts and ideas and providing an additional opportunity to develop higher-order thinking skills.

For example, an area model representing ¾ may be easier for students to understand than a set model (e.g., three red toy cars in a bag of four toy cars). However, teachers can encourage students to connect the two models by understanding the whole and identifying the unit fraction (¼) in both models.

To develop students’ higher-order thinking, teachers must encourage students to engage with multiple mathematical representations to explain their ideas and solve problems and provide opportunities for them to make connections among the multiple mathematical representations.

Model problem-solving steps and strategies. One of the Common Core Standards for Mathematical Practice is to make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. George Polya’s widely used 4-step problem-solving process (understanding and unpacking a problem, devising a plan and choosing appropriate strategies, implementing the strategies, and determining if the answers make sense) can be helpful in addressing the first component of the practice (Polya, 1945). It can give students a foothold toward approaching a problem, allowing them to not give up too early.

Explicitly modeling these steps and then, critically, cycling back to trying a different strategy if an answer is not correct will develop and enhance students’ mathematical thinking. When teachers demonstrate and explain each step of solving a problem, they make their thinking process visible, allowing students to see how more experienced mathematicians grapple with reaching solutions. This deepens their own understanding of problem solving and, perhaps more importantly, enhances their confidence in doing it.

Additionally, teachers should encourage their students to solve problems in various ways and make connections among different solution methods. This is another way to help students deepen their conceptual understandings, improve their ability to think mathematically, and develop their creative thinking in mathematics.

Engage students in mathematical discourse. New knowledge and skills are constructed and developed through interactions with peers and teachers. When students engage in mathematical discourse, they have opportunities to reason and critique others’ reasoning, construct and justify their own arguments, communicate their ideas, and reflect upon their thinking (Smith & Stein, 2011). Teachers can facilitate whole-class conversations around solving a problem and invite students to share and discuss their different solution methods, encouraging them to find connections among their methods. Students can also discuss their ideas in small groups or partnerships. It is important that students make connections among the different ideas or solution methods in discussions. For example, there are at least three methods for addressing ratio and rate problems: drawing a ratio table, finding the unit rate, and setting up an equation. Students can make sense of the three methods as they discuss the similarities and differences among them, thereby strengthening and developing their higher-order thinking in mathematics. Besides the oral discourse in the classroom, teachers also can create opportunities for students to explain and demonstrate their ideas and solution methods in written words or pictures, allowing students to deepen their higher-order thinking in mathematics. Precise written communication requires thinking with concepts, thinking critically, and thinking with rules. Engaging in mathematical discourse around written work provides opportunities to uncover misconceptions and errors, as well as to reflect on them.

Final Thoughts

Artificial Intelligence (AI) will play an increasingly critical role in society and education. Faced with the uncertain opportunities and challenges brought about by AI, developing students’ higher-order thinking in mathematics is tremendously important. Students need the ability to think conceptually, critically, and creatively in mathematics when evaluating mathematical ideas and solution methods produced by AI. Meanwhile, teachers need to explore how they leverage AI to strengthen students’ higher-order thinking in mathematics.

References

Barringer, M. D., Pohlman, C., & Robinson, M. (2010). Schools for all kinds of minds:Boosting student success by embracing learning variation. Jossey-Bass.

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common Core state standards for mathematics.

Polya, G. (1945). How to solve it: A new aspect of mathematical method. Princeton University Press.

Smith, M. S., & Stein, M. K. (2011). 5 practices for orchestrating productive mathematics discussions. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

The contents of this blog post were developed under a grant from the Department of Education. However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Math for All is a professional development program that brings general and special education teachers together to enhance their skills in

planning and adapting mathematics lessons to ensure that all students achieve high-quality learning outcomes in mathematics.