Supporting Students with Limited or Interrupted Formal Education

by Annie Smith

Years ago, I worked in classrooms and in after-school settings with refugee youth at a school that was established specifically for students newly arrived in the U.S. The teachers who founded the school in the Bronx promoted literacy as a means to help students succeed in their world. They were skilled and reflective practitioners. They designed project-based curricula that allowed students to draw on their personal backgrounds, and understood how to integrate language and content in ways that were engaging for adolescents. Yet as rich and thoughtful as the curriculum was, a subset of students challenged their competence. These Multilingual Learners (MLLs) were designated as Students with Limited or Interrupted Formal Education (SLIFE). New York State defines this population as:

“English Language Learners (ELLs) who have attended schools in the United States (the 50 States and the District of Columbia) for less than twelve months and who, upon initial enrollment in such schools, are two or more years below grade level in literacy in their home language and/or two or more years below grade level in Math due to inconsistent or interrupted schooling prior to arrival in the United States.”

Although the definition raised our awareness of this subset of students, it oversimplified who they were. The students we served were often significantly more years behind grade level than the minimum number included in the state definition, and certainly more than what our professional training prepared us for. Some never went to school but contributed to family life by holding a job, tending to children, cooking, planting and harvesting on a farm, or selling crops in a market. Others went to school where the day lasted only a few hours because teachers rarely showed up, classes were overcrowded, and/or resources were limited. Some left school to work because their schools were destroyed in regional conflicts. Many had spent more than a third of their lives protecting themselves from war or the terror of gangs. Many were students who had not yet consolidated foundational literacy and numeracy in their home languages. They were students with strengths in a variety of areas yet minimal or no experience with formal education.

Deborah Short and Shannon Fitzsimmons’ seminal 2007 report on adolescent language acquisition and literacy for MLLs describes this population as facing “Double the Work” of their peers. Not only do MLLs have to learn grade-level content, but they must learn it in a language they do not yet speak or have not yet mastered. Using Short and Fitzsimmons’ phrasing, I would argue that SLIFE learners in our classrooms face triple the work because, in addition to the language and the content for which they often have no previous conceptual framework, they must also learn the academic ways of thinking on which formal education is premised.

Andrea DeCapua and Helaine Marshall have made significant contributions to understanding SLIFE populations by pointing out the differences between the informal learning paradigms that many come from and the formal learning paradigm they encounter in U.S. classrooms. Their Mutually Adaptive Learning Paradigm (MALP) recommends that educators understand the overarching distinguishing features of each and design learning experiences that explicitly bridge the two.

Informal Learning |

Formal Learning |

|

Conditions for Learning |

Immediate relevance

Interconnectedness and interdependence |

Future relevance

Independence |

Processes for Learning |

Oral transmission

Shared responsibility |

Written word

Individual accountability |

Activities for Learning |

Pragmatic tasks based on lived experiences | Decontextualized tasks based on academic ways of thinking |

Adapted from DeCapua’s and Marshall’s MALP Instructional Approach.

SLIFE tend to be accustomed to making sense of their environment in contexts where information is immediately relevant. In formal learning contexts, project-based units that are grounded in real-life experiences do this well. Secondly, it is helpful if teachers offer learning paths that combine multiple processes for learning, providing ample opportunity for collaboration and oral negotiation of meaning as well as the individual accountability that is often part of formal educational settings. Finally, SLIFE benefit when teachers explicitly teach academic ways of thinking and make decontextualized, abstract tasks more accessible by pointing out when information is represented in symbolic or implicit ways.

The MALP can help teachers consider a student’s prior experience with formal school and offer strategies derived from informal learning experiences that can be used in a lesson to reduce barriers to classroom learning, similar to how Math for All’s Neurodevelopmental Framework (NDF) can help us to better understand the cognitive, language, and social strengths and challenges that play a role in students’ ability to engage with and understand content.

A Middle School Example

Let’s look at how we can use Decapua and Marshall’s MALP and the NDF to increase mathematical access for students who need extra support with accessing language in mathematics problems.

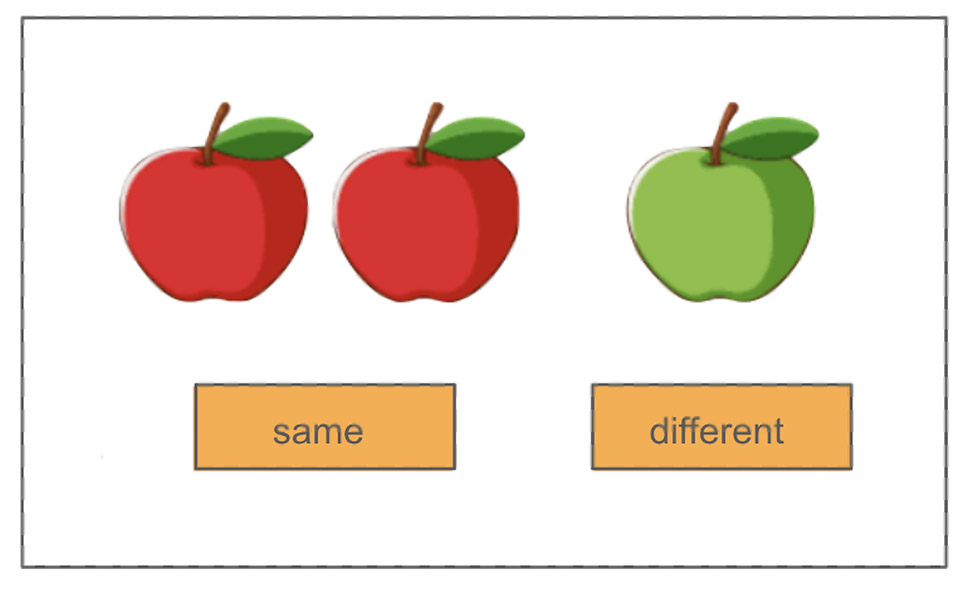

In section 1.2 of the teacher’s guide from Illustrative Mathematics’ lesson on equivalent ratios, the teacher prepares three mixtures using the proportions of water and powdered drink mix shown in the image and then students are to respond to the questions below it.

- Which mixture tastes different? Describe how it is different.

- Here are the recipes that were used to make the three mixtures:

- 1 cup of water with 1½ teaspoons of powdered drink mix

- 2 cups of water with ½ teaspoon of powdered drink mix

- 1 cup of water with ¼ teaspoon of powdered drink mix

Which of these recipes is for the stronger tasting mixture? Explain how you know.

Adapting the Task with Students’ Learning Profiles in Mind

A one-size-fits-all approach cannot support a range of students’ needs and so we must keep individual learners in mind as we consider ways to adjust lessons and activities. Each student, whether categorized as a SLIFE or one who has always been in formal educational settings, comes to classrooms with strengths and challenges. Through observation and interaction across a range of activities, we learn about the background knowledge, experiences, and skills that individual students bring to the tasks we present. Over time, learning profiles begin to emerge that can guide us as we consider ways to adapt lessons that build on individual student strengths and scaffold areas that are challenging, increasing entry points for ranges of students.

Let’s imagine a SLIFE student in the 7th-grade math class that will be engaging in the ratio activity. This student has been in the U.S. for six months and has demonstrated significant perseverance while adjusting to a new country, culture, and language. He attends school daily, attempts to connect with peers, and is eager to learn, particularly when content aligns with his interest in cooking and food. The student has beginner-level conversational skills in English and struggles significantly with middle-school vocabulary and academic English. His reading comprehension is limited but he recognizes some common words and phrases.

The introductory ratio activity aims to elicit students’ understanding of equivalent ratios; when we add one scoop of a powdered drink mixture to a cup of water it will taste the same as adding two scoops to two cups of water. Students are asked to consider the mixtures and the recipes used to create them as they think through responses to the questions.

When considering adaptations, teachers can quickly recognize the extensive receptive and expressive language demands of the task, noting the many vocabulary words one must know to understand the picture and the questions. Using the MALP as a guide, however, we discover that the activity also uses abstract representations, highlighting contextual and cultural differences between learners who have experienced formal schooling and those who have not. For example, the activity requires one to understand the concept of a diluted solution and abstract that the different colored mixtures signify this. Students must also be able to read the words and understand fractions and recipes as noted in the labelled image.

The table below breaks down the introductory ratio activity and suggests adaptations that can help bridge the gap between the skills used in informal settings and those present in formal learning conditions by adding relevance and context and offering vocabulary.

Original Task |

Suggested Adaptations |

| Your teacher will show you three mixtures. Two taste the same, and one is different. | Before the lesson, introduce the words same, different, and taste.

Use multiple visuals to represent the ideas of “same”, “different”, and “taste”.

|

| Which mixture tastes different? Describe how it is different. | Teach the word mixture while adding the drink mix to the water.

Ask students to share their experiences with making drinks. |

Here are the recipes that were used to make the three mixtures:

|

Set up the activity with real glasses, powdered drink mix, and water.

Make the drinks with the class and show the stages of making the drinks, teaching cup, teaspoon, and water in context. Give students the opportunity to mix the drinks, either in addition to, or as a replacement for, a teacher demonstration. |

| Which of these recipes is for the stronger tasting mixture? Explain how you know. | Use taste, same, and different taste to describe the drink mixture.

Provide sentence frames, keeping the vocabulary consistent (avoiding the word stronger, for example): Mixtures ___ and ___ will taste the same. Mixture ___ will taste different than mixture ___ and mixture ___. Newcomers who write in their home language can provide an explanation in that language. For students who do not write in their home language, they can explain orally to you or to a partner who shares the same language. This can help you assess conceptual understanding. |

Gradually and explicitly teaching the abstract ways that information is presented, anchored by concrete, tangible materials or objects, and building and reinforcing the skills that are necessary to meaningfully grapple with concepts will allow teachers to discover how to balance the academic expectations of formal classrooms while building on the learning profiles and breadth of experiences that students bring with them. Using the MALP can help us attend to the formal and informal characteristics of a given task and identify strategies that are more finely attuned to individual students’ learning profiles, in an effort to provide access to high-quality mathematics to more learners.

References

DeCapua, A., & Marshall, H. W. (2011). Reaching ELLs at risk: Instruction for students with limited or interrupted formal education. Preventing school failure: Alternative education for children and youth, 55(1), 35–41.

Marshall, H. W., & DeCapua, A. (2013). Making the transition to classroom success: Culturally responsive teaching for struggling language learners. University of Michigan Press.

Short, D. J., & Fitzsimmons, S. (2007). Double the work: Challenges and solutions to acquiring language and academic literacy for adolescent English language learners—A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York. Alliance for Excellent Education.

The contents of this blog post were developed under a grant from the Department of Education. However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Math for All is a professional development program that brings general and special education teachers together to enhance their skills in

planning and adapting mathematics lessons to ensure that all students achieve high-quality learning outcomes in mathematics.