Translanguaging & Math

By Amy Withers

October is designated as Celebrate the Bilingual Child Month, and we take this opportunity to recognize and celebrate all the strengths that multilingual children bring to the classroom and to highlight some practices that can support these students in math.

In the United States, about 10% of school children are English Learners (ELs). It’s important to note that EL refers to students who are in the process of gaining English proficiency but does not include the millions of students who are bilingual or multilingual and have gained English proficiency, having formerly been classified as ELs. ELs are a diverse group of students, representing many different school experiences, languages, academic strengths, cultural norms, and more. In this blog, I will refer to multilingual learners in recognition of the many students who speak two or more languages and who may be current or former ELs.

As with all students, using the Neurodevelopmental Framework with multilingual learners helps us frame their strengths and areas of growth within the various learning lenses that impact learning. An important part of supporting multilingual learners is recognizing and celebrating all of the linguistic knowledge they bring to the classroom. One important way of doing this is to practice translanguaging. Simply put, this means recognizing that multilingual learners bring a full linguistic repertoire to bear in any given context and honoring and using a multilingual person’s full linguistic repertoire.

As someone who is bilingual, I’ve been practically translanguaging ever since I learned a second language as an adult. My second language, Spanish, became a part of my language repertoire along with English, my home language. I found myself speaking in one language, but thinking of words in the other language. I code-switch, of course, and move from one language to the other depending on what most fits the context. However, translanguaging differs from code-switching in that I am not consciously switching from one language to the next, but simply using all of the language that I have at my disposal. We don’t separate out the two or more languages that we know, and we often use both at the same time. I notice this most when I am having a conversation with an English-only speaker and come to a place where I want to use a word in Spanish and stop myself (or sometimes not!) so as to be understood by my conversation partner.

Similar to the Math for All framework, translanguaging is asset-based in that it recognizes all the strengths of multilingual students and builds on those to develop both language and content. In translanguaging, the goal is not to replace any language with English, but rather to add to a student’s linguistic repertoire holistically. In fact, by allowing students to use their home language while engaging in English, we support their developing understanding of both content and language. There are some parallels here between translanguaging and language development more broadly, in that while students are developing academic language, they will use the language they have at their disposal to express their ideas.

A lovely example of this is found in a video case study we use in a lower-grades Math for All Workshop that focuses on language. As the focal student, Ephraim, is working with some attribute blocks, he describes one of them as “spiky.” Though he doesn’t yet have corners or vertices as part of his vocabulary, he is describing the shape in a way that makes sense to him and can be understood by others.

The Math for All framework reminds us of the various aspects of language that effect learning: understanding and using content-specific language; using language to communicate with others and clarify ideas; using language to develop and master abstract concepts; and demonstrating higher language function. In addition to these learning areas, we also need to support receptive and expressive language, both orally and in writing. Although it may seem overwhelming to think about supporting language development in more than one language, our understanding of one language system supports our acquisition of other languages.

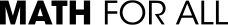

So how might we use translanguaging in the classroom? And what if we don’t speak any language other than English? The good news is that one doesn’t need to be bilingual or multilingual in order to use translanguaging as pedagogy. When we don’t share a language with a student we are teaching, we can sometimes make false assumptions about the prior knowledge, experiences, and so on of our student. We want to bridge the language gap between ourselves and our students so that we can get a clearer picture of our students’ mathematical thinking. Here we offer a few ways to get started. The Regional Educational Laboratory (REL) Pacific created the helpful infographic below that outlines some of the basic tenets of and strategies for using translanguaging in the classroom.

First and foremost, it’s important to welcome and honor all languages spoken by students in the classroom. Learning greetings in the home languages of your students can go a long way toward establishing trust and rapport in a multilingual classroom. Modeling the use of various written and spoken languages in the classroom signals that all languages are welcome and normalized within a school setting. Likewise, we have to ensure that students feel comfortable using all of their languages, not just English, while in school. Another way to honor students’ languages is to allow choice in the language used for some assignments, as suggested above, and displaying student work in both or several languages.

Key to developing language for any child is many supported opportunities to use language. Oral language development is a vital part of learning. We want students to have many supported opportunities to express themselves in both their home language and in English. Here is one way this might look in a math classroom:

- Pair students who share a language.

- Give students a word problem written in English as well as in their home language (or use an app to translate the problem orally into their language).

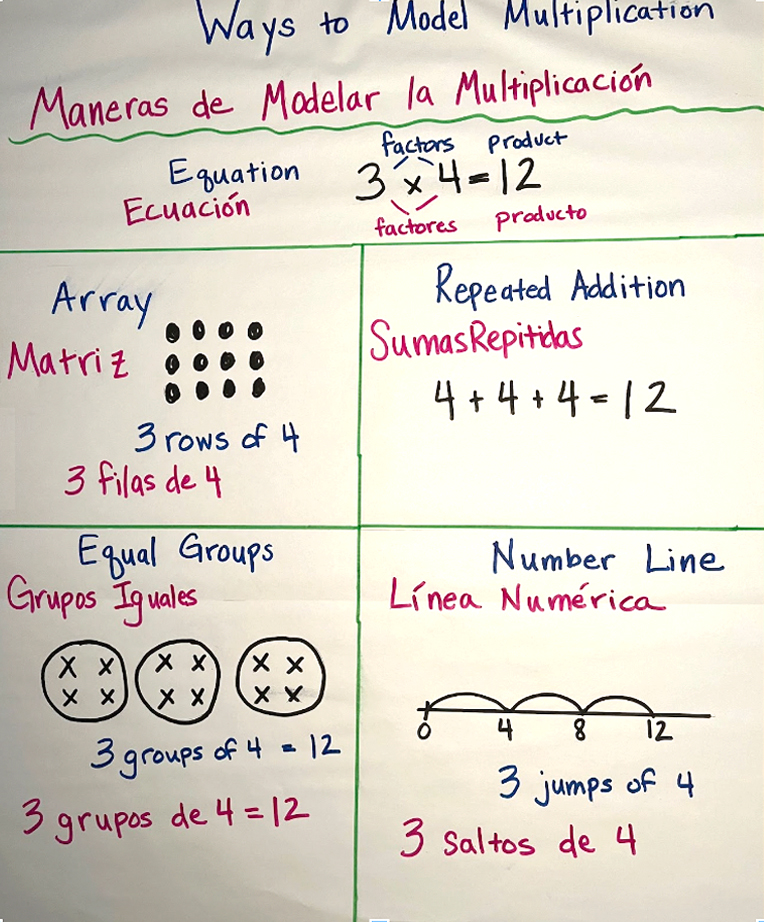

- Provide bilingual glossaries, word banks, and anchor charts.

- Provide sentence frames in English.

- Allow students to discuss, take notes, and annotate in their home language as well as in English.

- With the provided structures, you may ask students to present their work bilingually with a partner who can help translate in English when needed—both in writing and orally.

Use technology! There are many apps that can provide instant translation for conversation and can easily help others gain a better understanding of a student’s thinking. This can allow you to more easily confer with students as they work on math problems. It’s also a chance for us teachers to increase our knowledge of key math vocabulary in the language(s) of our students. A recent NCTM article, “Translanguaging Pedagogy in Elementary Mathematics,” explores how one teacher successfully uses technology with her early elementary multilingual students. Google Translate is a great option to translate written text into many languages. With any translation technology, there will always be mistakes. It’s good practice to check in with the multilingual learners in your classroom to ensure the translation makes sense, and they may be able to help you make corrections where needed. Remember that not ALL text needs to be translated ALL the time—focusing on the key content and vocabulary for translation can provide access for students.

Lastly, just as when we are planning accommodations in the Math for All framework we do not reduce the rigor of the mathematics, we do not want to change the rigor of the math for our multilingual students. We want to provide access to mathematics as well as gain opportunities to better understand our students’ mathematical thinking. Using translanguaging as a pedagogical tool is one way to provide that access and gain that understanding while maintaining the rigor of the mathematics.

Further Reading

CUNY-NYSIEB: Initiative on Emergent Bilinguals

Sánchez, M. T., & Garcia, O. (Eds). (2021). Transformative translanguaging espacios: Latinx students and their teacher rompiendo fronteras sin miedo. Multilingual Matters.

Willging, T. M., & de Oliveira, L. C. (2023). Translanguaging pedagogy in elementary mathematics. Mathematics Teacher: Learning and Teaching PK-12, 116(8), 586–591.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). English Learners in Public Schools. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Science.

The contents of this blog post were developed under a grant from the Department of Education. However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Math for All is a professional development program that brings general and special education teachers together to enhance their skills in

planning and adapting mathematics lessons to ensure that all students achieve high-quality learning outcomes in mathematics.